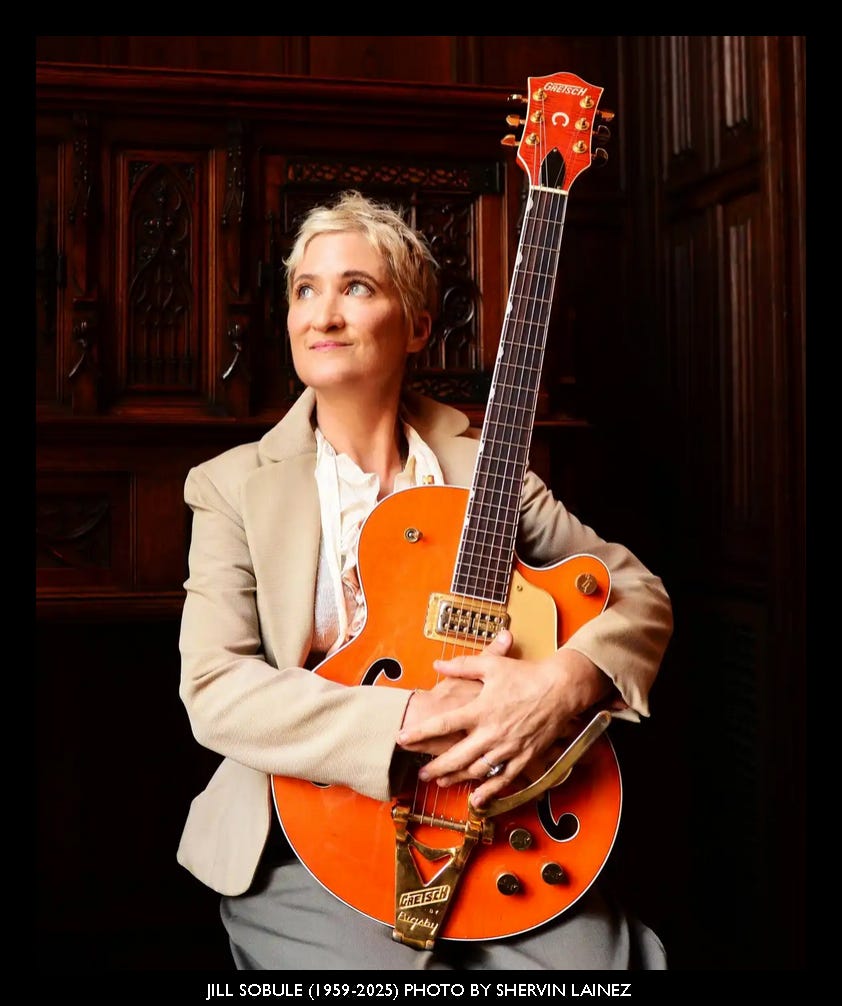

As a deeply human human-being, Jill Sobule may have felt like the underdog at times, but in the way she lived her far too brief life, she was victorious.

Last Thursday afternoon, while I was waiting to hand over $2400 to a mechanic for service and maintenance of my car, I randomly looked down at my phone and saw a post from my friend and colleague, the Cleveland based music journalist Annie Zaleski: “What terrible, devastating news to get PR that Jill Sobule died in a house fire this morning. She was just in Ohio last week with the Fixx. Such a witty and smart songwriter.”

As I stood there, stunned, I suddenly cared far less about the big money I was about to fork over to my Mini dealer. I couldn’t summon the appropriate words, so I think I just commented “NO!” on Annie’s post. I left a few similarly unsatisfactory comments on many of the subsequent social media posts that began to go off, like popcorn popping, as the awful news reverberated not just within my musical community, but around the broader political and social justice networks that inform and inspire me, day in and day out, in this cursed time.

The tragic news hit a lot of us hard because, to many, Jill Sobule was more than just a gifted, witty, and socially conscious singer songwriter. She was a vibrant, empowered, and empowering soul who touched everyone who ever came in contact with her keen wit, boundless charm, and innate empathy.

I should point out here that I never met Jill in person, but we chatted online occasionally, sometimes in a public reply thread, sometimes in emails or DMs. Yet I know so many people whose lives were lifted, and spirits raised in the warmth of her light, and I am sad that I will never share one of those IRL moments. Still, for those of us who never had the pleasure of her company, her radiant humanity was right there, beaming out from the songs.

My first exposure to Jill’s music came when she was the opening act for Joe Jackson at Toronto’s Massey Hall on his Laughter & Lust tour. According to Setlist FM, the date was July 24, 1991, and Jill played solo, mainly featuring material from her Todd Rundgren produced debut album, Things Here Are Different which had just come out the previous year. (I later learned that Joe and Jill had been collaborating at the time on what was to be her sophomore album, but she was dropped from her label before it saw the light of day.) Back at Massey Hall, the first song to catch my ear in her live set was the mildly samba inflected “Too Cool To Fall In Love,” but the one that really stayed with me was a song that she had hoped would be on her next album.

“Karen By Night” was based on Jill’s real life day job at a shoe store on 7th Avenue in New York. In the song, she speculates on the private life of her seemingly square boss, Karen. In what I believe was Jill’s fictionalized version of events, after overhearing an intriguing conversation, our narrator follows Karen into her post 9-5 underworld where she discovers that Karen leads a far more adventurous and romantic parallel life after hours, describing Dark Karen as a leather-clad, red lipstick wearing renegade who hops on her motorcycle looking like Marlon Brando, clarifying with a comic pause, “like a young Marlon Brando.” The inventiveness of the tale, and the witty asides, instantly told me so much about her. I made a note to myself to check out her album.

If you have read my book about Todd Rundgren’s record production career, you may have noticed that there was little more than a passing reference to Things Here Are Different. That wasn’t an intentional snub on my part, I really like the album, but the minimal coverage was the result of both editorial sacrifices (the first draft of my manuscript was three times too long for my editor) and scheduling issues. After obtaining in-person interviews with many of Rundgren’s better known clients, such as the entire Patti Smith Group, XTC, most of the principals involved in Meat Loaf’s Bat Out Of Hell, both Hall and Oates, most of the Tubes, and the surviving New York Dolls, I didn’t get everyone. By deadline time, I had failed to locate people like Fanny’s June Millington, who I only managed to contact long after the book had been printed. And despite what my email history shows as my persistent attempts, Jill Sobule never went on the record with me for the book.

Now, I had heard from a secondary source that Jill had not especially enjoyed working with Todd (which, to be frank, had been the case with some of Todd’s other clients, famously including Andy Partridge from XTC), and I could see how Todd’s notoriously firm board-side manner might have intimidated a first time recording artist at such a delicate time in their career. But again, I never heard any of that directly from her, so who knows? But going by that assumption, my first email approach sought to reassure her that I wasn’t attempting to write a hagiography here, and that even an unpleasant tale was worth adding to the fabric of my book.

To my surprise, she initially seemed up to talking with me about it, and even gave me her home phone number with instructions to call back and set up a date and time to chat. But only a few days later, she emailed to say she was “sick as a dog” and would like to reschedule. Of course. Maybe I had been wrong about it all. But in the ensuing months, and after three more unsuccessful attempts at rebooking the interview, I concluded that she had gotten cold feet and simply didn’t want to speak of it, ill or otherwise, which was, of course, her prerogative.

Years after my book came out, I read somewhere else that while Jill had indeed been in what she referred to as “a bit of a rough patch” during the Rundgren sessions, and found the overall experience “weird,” her only enduring issue with Things Here Are Different was that it was a document of a time before she had discovered her true artistic voice. But then again, a few years later still, I read that she could now appreciate her debut for what it was and didn’t hate it at all. Significantly, for me, none of this seemed to affect my future interactions with her. In fact, my private messaging history from the later years shows that Jill and I engaged in a few decidedly friendly correspondences from time to time. In 2014, she thanked me for sending her a copy of my album, Inner Sunset by The Paul & John (my duo with John Moremen).

Still, I always wished I could have done an updated version with more background on Jill’s album (and Fanny’s), but even if I one day get the greenlight for such an expanded and updated edition, which could happen, I will regrettably never get the story directly from Jill.

While Jill’s debut didn’t really make much of a dent in the marketplace, her 1995 self-titled album (produced by Brad Jones and Robin Eaton, who really did help her find that voice) certainly did. Jill Sobule, the album, yielded superb tracks like “Supermodel,” (commissioned for the Clueless soundtrack and not her own song) but perhaps more significantly, “I Kissed A Girl” which was a kind of “coming out” song as both a mainstream video star and as a Queer artist. Besides predating the similarly named Katy Perry song by a good thirteen years, “I Kissed A Girl” changed her life (and I suspect the lives of many people in the LGBTQ community; the AP recently described it as “the first openly gay-themed song ever to crack the Billboard Top 20”). I was also delighted that the album finally gave us a great studio recording of the song that had caught my ear back at Massey Hall, “Karen By Night.”

Over the years, I was glad I got to tell her about two more of her songs that deeply affected me.

As a sometimes frustrated musician feeling beaten down by my attempts to “make it” in the big, bad music business, her song “Bitter,” a single from her 1997 album Happy Town, not only spoke to me, but I’d also wager it damn near saved my life. The music business is littered with well-intentioned but emotionally insecure artists who feel betrayed by circumstance and devolve into jealousy and bitterness, killing the so-called golden goose in the process. But here was Jill Sobule, who I’m sure had endured her fair share and more of hard knocks along the road, raising a banner for letting go of the toxic energy that kills the soul:

“I don't want to get bitter

I don't want to turn cruel

I don't want to get old before I have to…”

In case the message was too subtle, the biggest clue was right there in the last verse:

“So I'll smile with the rest

Wishing everyone the best

And know the one who made it,

Made it 'cause she was actually pretty good.”

On a different note, she later pulled off an incredible feat by sampling Chicago’s “Saturday In The Park” and then writing a whole new, and possibly better, song over the top of it. And the song was actually pretty good! “Cinnamon Park,” from her fantastic 2004 album Underdog Victorious, told the story of innocent summers of youth, discovering the joys of smoking “mother nature” at a summer battle of the bands. An older boy coaxes her and her pal Betty into the back of his van and offers them their very first joint.

“Cinnamon Park in a cinnamon daze,

We were so freaked out

But in a really good way.

In a really good way

Yeah those were the days.

I wish I could go back again.”

Trading on the sampled nostalgia of the Chicago tune to tell the nostalgic story of a smoky ritual rite of passage was something that a lesser songwriter might have botched completely, but Jill Sobule pulled it off. I think it’s one of her best songs.

Jill Sobule was an activist for social change, she was an incredibly talented songwriter, she could be funny and fun, but she never backed away from serious causes.

Jill Sobule shouldn’t have died so young, and certainly not in the way she did. In her time here, she affected me greatly, even though I never met her in person. Take a look at the people who did know and love her and see what those who mourn her deeply are saying today.

She radiated life, and generated love. She gave us the songs. She did the work.

And I for one, thank her.